Charles C. Comstock, Civil War Days and After

THE CANAL, THE DAM, THE RIVER

Just before I undertook to clear up the Bronson Mortgage, I had contracted with Daniel Ball for the bed and banks of the Canal above the mill site I purchased from him, and had him deed to the Water Co. without conversation, the premises where the guard gates, the waste run, and dam, to the center of the river; guard gates being where they now are; and all his front on Canal St. to the center of Coldbrook St., and to the center of Grand River, for $1200. When we did clear up the Bronson Mortgage I agreed with him to have that money applied on the mortgage. The Canal Co. had the right to draw water through the canal, and that was all that was reserved in this purchase, except the right I had purchased in 1856 and paid him $2000, for right of dockage for 500 ft. opposite the Pail Factory and yard. This last purchase was an extraordinary one, as I immediately sold to Wm. Morman for $1000 the strip of land between the west side of Canal St. and the river, from South line of Mason St. to center of Coldbrook St., reserving all rights of boomage opposite.

He afterward took into partnership a Mr. Hill and they commenced to make more land by filling into the river. I notified them that before they filled into the river they must buy the right. Hill said he had all the right he wanted, and should fill in all he chose to. I secured an injunction and the matter was in the courts for several years until Hill had failed and left the county, and I had beaten Mr. Morman in the suit.

I then proposed, what I would have done at any time, and I gave him the right to fill 80 ft. back from the west line of Canal St. half way from the south line of Mason St. to the center of Coldbrook St., he taking the south half, I keeping the entire upper half and right of way for a RR and log channel next to his 80 ft. on the south half. Had it not been for Hill, I have no idea that Mr. Morman and I would have had any trouble. I had but the kindest feelings towards him.

When the new dam was built, it was necessary to open the way into the pond at the guard gates, and there would be no further use for the canal above. I made a proposition to the Power Co. to do the work and put in the wall, I giving them the right of way into the pond, and they relinquishing their rights to the canal above. After this I commenced to fill up the canal and build a dock on the riverside, but only a few feet beyond the original bank of the river, as there was quite a strip of the bank remaining west of the canal that had never been disturbed.

COMSTOCK LOSES HIS FAMILY

In Oct. 1863, after selling ½ of my furniture manufacturing business, I left my son Tileston, then 19 years old, in charge of my interest there, giving him one-half the profits and boarding at home. I aided in advice, but not spending all my time there. In August 1865, after Alzina, her child, and husband were lost, but before I started for California, I sold my interest, one-half to Tileston and one-half to J. A. Pew and Manly G. Colson, two foremen in the factory and finishing rooms.

Tileston, then 21 years old, had saved by the profits in the business for two years nearly enough to pay for what he purchased of me, ¼ interest of the whole concern. He was married in Oct. 1865, while I was in California, to a daughter of Aaron B. Turner. His health was never robust, but he had excellent business judgment, always pleasant and agreeable and had many friends. I afterwards gave his three lots opposite my own residence and aided him in building his residence. He had the general supervision of my business while I was away three month in California

His health became more feeble and in the spring of 1869 he went to Colorado where it seemed to improve rapidly. He returned to Grand Rapids in August thinking that he had nearly recovered. He was taken down so suddenly that we started him back again in three weeks. He went to the hot springs, 50 miles from Denver, with his wife and child. He did not improve, and I, learning of his condition, visited him in Jan. 1870; stopped with him a week or so, and concluded that he had better go to California. He went to Southern California, until April, when he returned to Grand Rapids. It was evident that his life was about over. I consulted with him in regard to his business affairs, and we decided it to be best to dispose of his interest in the furniture trade, which I sold to Elias Matter for $40,000. He died with consumption Sept. 16, 1870.

Note: Even though ill, Tileston registered to vote. We have verification of Tileston A. Comstock, age 26, New San Diego, San Diego, California in voter registration records. “California, Great Registers, 1866-1910, film number 977094, page 5.

I did not wish to act as his administrator, and his father-in-law, Aaron B. Turner was appointed. I turned over to him $33,000 of well-secured paper, drawing ten per-cent annual interest, their residence and other property making $40,000 above any claims.

My first wife, Mary Winchester, died of consumption in December of 1863.

COMSTOCK, ALBERT BAXTER, AND LOGGING

At the time Elias Matter left me, Oct. 1, 1862, Albert Baxter came into my employ. He demanded only $6 per week for his services and board himself. He was much in need of a situation, although he had no one to support except himself. He intended to be faithful in all he did, but not efficient. I kept him as clerk, and in purchasing walnut logs and lumber. In the fall of 1864 I contracted with Benjamin Saules of Muir for one million feet of pine logs on Fish Creek to be put in next winter. I gave Baxter a copy of the contract and sent him to scale the logs. The logs were to be of as good quality as could be found in a body of that mount upon that creek, and to be put in at a point from which the creek had been cleared for that purpose, of running logs. I had raised Baxter’s wages from one dollar to three dollars a day, up to this time. I had never seen the timber on the place when the logs were being delivered. Baxter received the logs, at a point four miles above, where the creek had been cleared for the purpose of running logs. When I visited the camp in Feb. 1865 I found the logs were not the quality agreed on. I notified Saules at once, and he claimed that when they were all in, the logs would be up to the contract, and he claimed further, that as Baxter had scaled the logs as my agent, it was an acceptance of them under the contract. Had Baxter looked up and reported to me promptly the true condition, I should not have allowed him to scale the logs; as it was I was in a bad fix but I did not propose to be swindled in that way.

The logs being so far up the stream that it would cost several thousands of dollars to clear the creek. Saules, being a very haughty man, and in his own estimation, a very wealthy one, he excited others to join him in embarrassing me in getting out the logs.

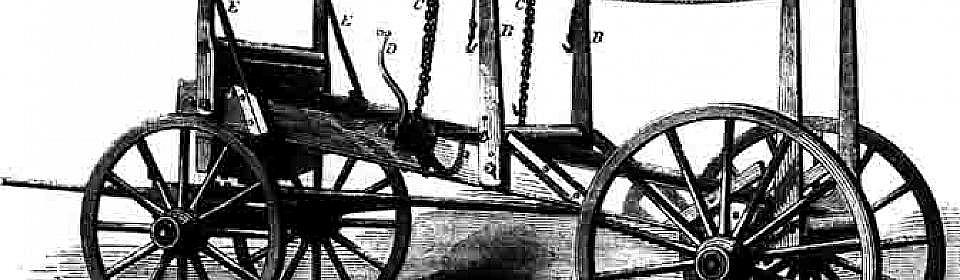

LUMBER RACK PATENT

In 1866 I built my sawmill on the Canal, and increased my lumber product and commenced to keep a stock of seasoned lumber. We were obliged to haul all our lumber from the mills to the yards on wagons. The distance was so great that it was impossible to clear it away from the mills as fast as sawed. I well remember studying one or two nights after I had gone to bed, to invent some process by which I could handle our lumber with more rapidity.

The outcome of this was I invented a lumber rack that did not require more than 30 seconds to unload and leave in a good pile. With these racks two men could be kept loading at the mill and one team would drive to the yard with a load and return with his empty wagon, take another load, and this one team and two men to load would handle as much lumber as would three teams. The new system broke less lumber and left it in better shape for piling.

This in my business was a very important invention, and I secured a patent in 1867. I have used them in my business since. At one time I had 13 of them in operation, and I think their use has saved me $50,000 in handling my lumber. After this invention, one Charles Stock, R. B. Woodcock, and W. H. Powers, each got up a similar rack for handling lumber, either of them an infringement on my patent, but I did not interfere with them. I sold the right to several parties to use my rack, but never made much effort to introduce it. I soon learned than many workingmen especially were opposed to the use of labor saving machinery. If their employers could afford to do without it, I could afford to let them.

FISH CREEK LOG RUNNING COMPANY

When I became fully apprised of the situation, I organized the Fish Creek Log Running Co., taking enough of the stock myself, to control the election of directors, and then went to work clearing the stream. It was very expensive and when we began to assess the cost upon the logs in the stream, the owners refused to pay their assessments. Baxter was the secretary and treasurer of the new company and had charge of the river, but he had neither the respect nor could he control the parties with whom he had to deal.

The company got in debt, although I had paid more than my assessments. The water was low and the head of the drive was only down to Hubbardston, the upper dam upon the stream, and here the work stopped. Fowler, of Detroit, owed over $2000 on his assessments. The Hubbardston Co. controlled by Wilson Horner, owed $1000, and smaller sums from others. There came rains in June, and I sent to Rouge River for about 20 of the best fighting log runners, who were efficient at either, and hired H. S. Waters as foremen, and hired J. W. Champlin as council. On our way to Hubbardston, stopped at Ionia and retained the law firm of Blanchard, Bell & Dodge, taking Dodge with us, and soon reached Hubbardston.

I first put the men from Rouge Rive with Mr. Waters in charge of the logs. I then, in the presence of Champlin and Dodge presented the bill of the Fish Creek Log Running Co. to Horner. He was a large man, and considered himself a man whose will was law, and no one could dispute his authority. As I presented the bill, he said, “Do you suppose I am such a dam fool as to pay that bill?”

I said to him, “Do you refuse to pay the bill?

He answered, “I do.”

I then asked him if he would lease us a portion of his booms and pond so we could hold possession of his logs till the matter was settled. His answer was a decided “No.”

I put the bill in my pocket, the lawyers started for the hotel, and I for the logs. About this time Horner began to see that his logs would soon be going down over his da, past his mill, and asked me if I thought I could drive his logs past his mill. I told him he had left us no other alternative. Said he, “You won’t do it. Come into this blacksmith shop as I want evidence that I forbid you.” I told him that we now have water to move the logs and no time to fool away.

I kept on my way to the logs, up through the woods, he sometimes in the path before me and sometime behind, very threatening in his demonstrations, and among other things, stated that he would drive my men from the logs. I told him that I had good men there, and what he said could not be done, and as for him, if he did not behave I would send to Ionia for the sheriff and his posse to take care of him.

When we reached the logs the men were dividing them and putting Horner’s logs in his boom. I spoke to Mr. Waters saying that we should not stop to divide the logs and to open the booms and drive the logs down the stream as fast as possible. Mr. Waters and the men obeyed with an energy that betokened business and skill.

When Horner fully realized the situation, although terribly excited, he said to me that he would settle that bill. I said, “Very well, go back to the hotel and settle it with the attorneys for that is what we are here for, and we deliver your logs into your pond.”

I purchased the land where my plat was afterwards located in the fall of 1867. At that time there was not 40 acres well-improved land between the Plainfield River Road and the River North of Leonard St. to Robert Briggs farm. This whole strip 2 ½ miles in length and containing more than a section of land was mostly in the hands of its purchasers from the Government.

Mr. Quimby had established his mill and two small sawmills with scarcely one acre for a mill yard, where the Filtration Plant now is. The highway was laid along the bank of the river, but it was never worked for travel.

I cleared up my entire plat of 118 acres, and put all east of what is now Canal St. into wheat in 1868. Soon after I platted these lands, and establish Canal St. with special reference to its connection with what is now Canal St. South, and the extension North which was completed by the building of the Gravel Road to Plainfield in 1884.

The railroad at the time of my platting was a solid embankment where Canal St. now is, and Solomon, Robinson & Co., Withey & Co., I.L Quimby, and I believe C.W. Coit, joined me and we hired the railroad company to open the highway under their RR and paid them $350, about half of which I paid myself, as I paid Mr. Quimby’s assessment, and he did not pay it back to me. The road was opened through Quimby’s and other lands, as a substitute for the road laid on the bank of the river, though they later claimed it was private property.

Excerpted from, Early Experiences and Personal Recollections of Charles Carter Comstock, written in Washington D.C. Begun January 4, 1887. Copied in 1936 by Etta Comstock Boltwood. Grand Rapids Public Library, Coll. #008

facebook

facebook